Untrusted customer code on the server with WebAssembly (Wasm) components

Key takeaways

- Security isolation when running untrusted customer code is complex and costly

- Multi-language support is even more complex

- The WebAssembly Component Model enables clean, language-agnostic interfaces between individual components and also hosts and guests, written as Wasm Interface Type (WIT) definitions

- Fuel metering, memory limits, and no I/O by default help mitigate risks like infinite loops or resource exhaustion from untrusted code

Why would I run untrusted code in the first place?

I’m glad I asked 😊. The simplest answer I can think of is that you want to allow your customers to extend your product with their own functionality. Think of a plugin system where you provide hooks in key parts of the process to execute customer-developed code.

A few examples come to mind:

- An e-commerce store allows its merchants to extend the checkout flow

- An ETL (extract, transform, load) pipeline runtime where customers upload code to process data

- An AI-infused video/image processing pipeline for digital content production

Project overview

In this blog post and the related GitHub repositories, we learn how to write a Rust Wasm environment that executes Wasm components uploaded via HTTP.

The Wasm components are expected to provide a run() function that is called by the server. The server on the other hand provides a log() function that Wasm components may use. This is the bare minimum to demonstrate how to execute functions in Wasm components and how to provide Wasm components with an interface to interact with the host system.

Repositories:

- github.com/mootoday/wasm-on-server-runtime-rust - The Rust server environment that executes Wasm components

- github.com/mootoday/wasm-on-server-guest-rust - The Rust Wasm component

- github.com/mootoday/wasm-on-server-guest-javascript - The JavaScript Wasm component

Architecture

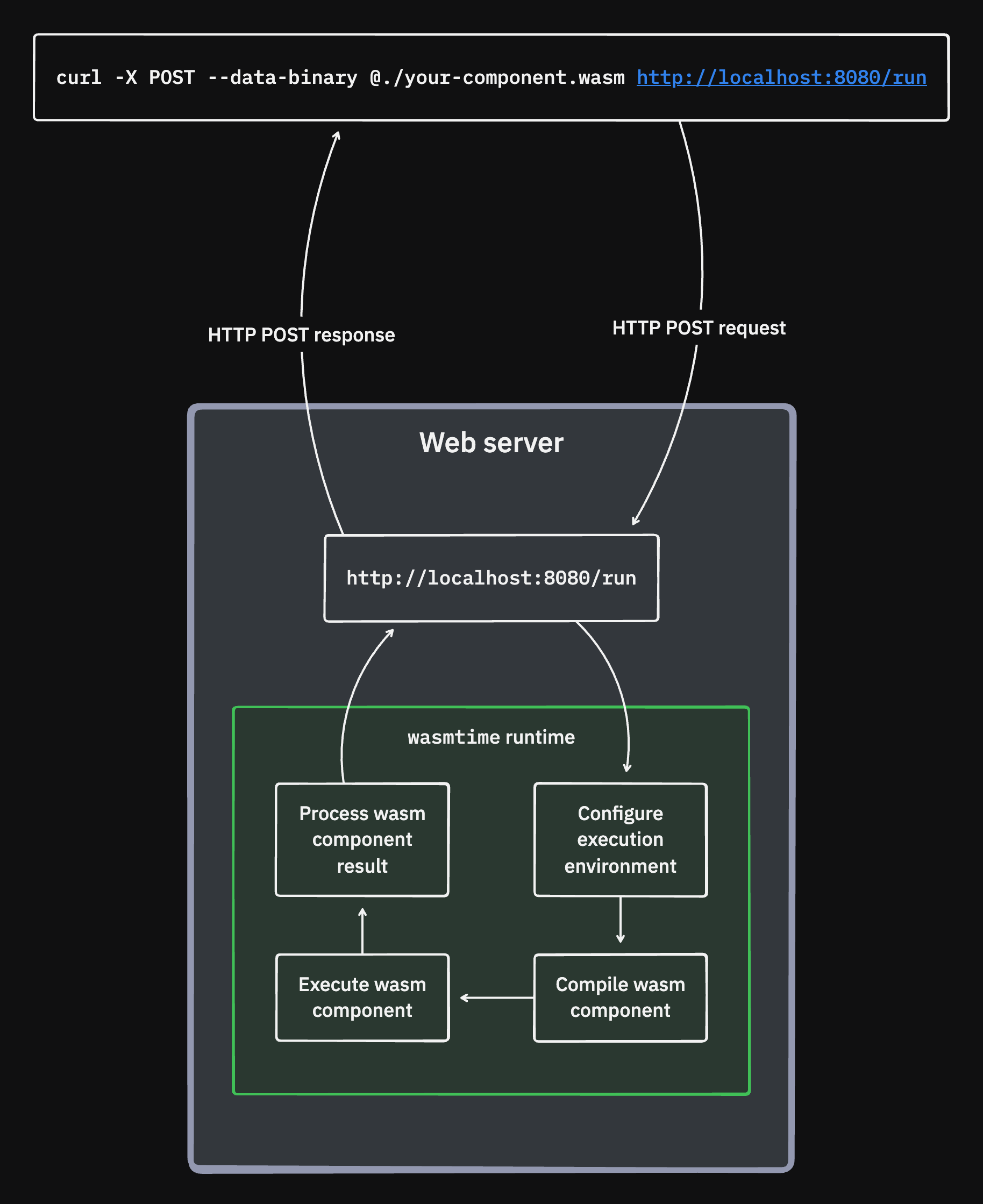

A curl command sends a binary .wasm file to localhost:8080/run. On the server, that Wasm component is compiled and executed in an isolated wasmtime runtime environment. Once complete (or cancelled because of errors or resource limitations), a response is sent back to the client, e.g. the terminal in the case of curl.

The Wasm component execution environment can be configured to avoid excessive resource usage by individual components. You know, to prevent someone from creating an infinite loop in their Wasm component to take down your entire system.

The web server

You can find the code for the Rust runtime (the “Web server” box in the architecture diagram above) at github.com/mootoday/wasm-on-server-runtime-rust. The code is well documented and self-explanatory, but let me walk through what happens at a high level.

The core of what the web server does is in the POST /run endpoint, which ultimately uses the runtime Rust file at src/wasm_runtime/runtime.rs.

The run_guest_component() function in that file expects two parameters of type AppState and Bytes. The app state only contains an Engine which is configured with various options in src/main.rs. This configuration is shared across all Wasm component executions.

run_guest_component() starts off by creating a new Store, which is unique for each Wasm component execution. The store’s data, configured as the second argument to Store::new(), is where you can define per-component execution settings. Think CPU and memory limits, I/O restrictions, and also host functions made available to a given Wasm component.

Some components or customers may be allowed to consume more resources or access certain directories/files or make network calls, while others may be restricted from some or all of that.

Next, the function creates and configures a Linker. A Linker is used to provide host functions to components and link together multiple components. For the purpose of this blog post, we configure WebAssembly System Interface (WASI) and host functions.

With all that configured, it’s time to create a Wasm component. This happens by compiling the bytes the POST /run endpoint received into a Wasm component.

With the compiled Wasm component at hand, the server instantiates a runner for the given Wasm component. To do that, we create the runner and pass it the Store, the compiled Wasm component, and the Linker.

All that is left is to execute the Wasm component’s run() function and handle all sorts of errors that may happen.

Wasm Interface Type (WIT)

Now that we have a high level picture, let’s learn about WIT. Here’s the WIT file we use as part of this blog post:

// wit/world.wit

package local:[email protected];

interface host {

log: func(msg: string);

}

world runner {

import host;

export run: func() -> result<string, string>;

}This file is located in wit/world.wit and exists in the runtime repository and all guest implementations (e.g. Rust and JavaScript at the time of this writing). In a production environment, you would use the wasm-pkg-tools project (repository) to distribute your WIT (docs).

The WIT file defines a host interface with a log function, which is available to Wasm components. The implementation of that function lives on the server (see “Host functions” below). Wasm components simply call the function according to the generated types for their preferred programming language of choice.

In the runner world (learn more about worlds), a run function is exported. Exported functions must be implemented by Wasm components. This is the interface for the server to call a Wasm component and execute it.

Host functions

Where are host functions defined? Where is their implementation? How do Wasm components call these functions?

As we learned in the previous section about WIT, host functions’ interface is defined in a WIT file (e.g. log() in our case):

// wit/world.wit

interface host {

log: func(msg: string);

}The implementation of that lives in the server runtime. In particular, the Host implementation in src/wasm_runtime/runtime.rs for the HostComponent:

// src/wasm_runtime/runtime.rs

impl local::main::host::Host for HostComponent {

async fn log(&mut self, msg: String) {

info!("{}", msg);

}

}Since this lives on the server, you have access to the file system, network, databases, anything your heart desires. As you develop host functions, keep in mind that any parameter you define increases your attack surface. Just like in web development, always sanitize input. Do not accept a String command parameter for example and execute it as-is 😰.

In the Rust server runtime, the local::main::host::Host trait is generated by the following code towards the top of the src/wasm_runtime/runtime.rs file:

// src/wasm_runtime/runtime.rs

wasmtime::component::bindgen!({

path: "wit",

async: true,

tracing: true,

});Wasm components can call host functions like they would any other function. In the next chapter, we will learn how the Rust and JavaScript Wasm components that are part of this blog post execute the log() host function.

How to create a Wasm component

As part of this blog post, we have two Wasm component implementations. One in Rust, one in JavaScript. Any other language can be used as well (see Wasm Language Support).

Each example component’s run() function succeeds 50% of the time and fails 50% of the time. This showcases how to handle success and error cases.

There is also a commented block of code that tries to write to the file system. If you uncomment said code, the server runtime will throw an error since the Wasm components do not have the necessary permissions to write to the file system.

Rust

The source code for the Rust Wasm component can be found at github.com/mootoday/wasm-on-server-guest-rust.

The following code in src/lib.rs generates the necessary bindings based on the wit/world.wit WIT definition:

wit_bindgen::generate!({

path: "wit",

});The main piece of code is located in the src/lib.rs file, namely the impl Guest for GuestComponent implementation block.

You can find the run() function implementation that is called by the server runtime. You also see how the log() host function is called:

local::main::host::log("Logging from the Rust guest");JavaScript

The source code for the JavaScript Wasm component can be found at github.com/mootoday/wasm-on-server-guest-javascript.

The build:guest-types NPM scripts generates the necessary Typescript types based on the wit/world.wit WIT definition. This is then used in src/index.js.

The main piece of code is located in the src/index.js file, namely the exported run() function.

Host functions are called by importing them from the generated package:

import { log } from "local:main/[email protected]";

...

export const run = () => {

log("Logging from the Javascript guest");

}Next steps

Define CPU and other restrictions

You can interrupt the Wasm component execution in various ways, e.g. by limiting CPU usage or memory consumption. For details on how to do that, please see the ”Interrupting Wasm Execution” docs.

Pre-compile Wasm components

The current implementation compiles a Wasm component at runtime before it executes its run() function. Do not do that in production 😅.

Instead, read the Pre-Compiling and Cross-Compiling WebAssembly Programs docs. A production-ready architecture is to pre-compile Wasm components sent to the server, persist the pre-compiled *.cwasm file, then use that at runtime to execute its run() function.

What if…?

What if there were a platform that allowed you to visually define pipelines where each node represents a Wasm component?

For example, instead of limiting ETL processing to SQL, what if you could write Wasm components in your programming language of choice to process your data?

Meet wasmCloud! It’s part of the overall solution I’m going to explore next.

Contact me if that sounds like something you would use.

Conclusion

I looked into Wasm on and off for the last few years, ever since I learned that Figma is powered by Wasm (blog post).

However, it wasn’t until fall of 2024 when I realized Wasm worked on the server as well. Then earlier in 2025 I read an article about the Wasm Component Model, and that is when it really clicked for me.

Thanks to the built-in security features and the language-agnostic aspect, I think Wasm components on the server are an underrated technology worth exploring.

It definitely caught my interest. I am going to see what I can put together over the next little while in terms of a platform that runs pipelines based on Wasm components. In the worst case, I will learn a lot!

👋